Hinduism

Hindu beliefs include numerous varieties of spirits that might be classified as demigods, including Vetalas, Bhutas and Pishachas. Rakshasas and Asuras are often misunderstood to be as demons. There are no demons in Hinduism as hinduism is not based on good and evil and is not constructed by the principle of duality.

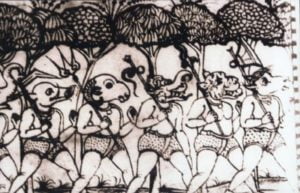

Asuras

Originally, Asura, in the earliest hymns of the Rig Veda, meant any supernatural spirit, either good or bad. Since the /s/ of the Indic linguistic branch is cognate with the /h/ of the Early Iranian languages, the word Asura, representing a category of celestial beings, is a cognate of Ahura (Mazda), the Supreme God of the monotheistic Zoroastrians. Ancient Hinduism tells that Devas (also called suras) and Asuras are half-brothers, sons of the same father Kashyapa; although some of the Devas, such as Varuna, are also called Asuras. Later, during Puranic age, Asura and Rakshasa came to exclusively mean any of a race of anthropomorphic, powerful, possibly evil beings. Daitya (lit. sons of the mother “Diti”), Rakshasa (lit. from “harm to be guarded against”), and Asura are incorrectly translated into English as “demon”.

Post Vedic, Hindu scriptures, pious, highly enlightened Asuras, such as Prahlada and Vibhishana, are not uncommon. The Asura are not fundamentally against the gods, nor do they tempt humans to fall. Many people metaphorically interpret the Asura as manifestations of the ignoble passions in the human mind and as a symbolic devices. There were also cases of power-hungry Asuras challenging various aspects of the Gods, but only to be defeated eventually and seek forgiveness—see Surapadman and Narakasura.

Evil spirits

Hinduism advocates the reincarnation and transmigration of souls according to one’s karma. Souls (Atman) of the dead are adjudged by the Yama and are accorded various purging punishments before being reborn. Humans that have committed extraordinary wrongs are condemned to roam as lonely, often mischief mongers, spirits for a length of time before being reborn. Many kinds of such spirits (Vetalas, Pishachas, Bhūta) are recognized in the later Hindu texts.

Bahá’í Faith

In the Bahá’í Faith, demons are not regarded as independent evil spirits as they are in some faiths. Rather, evil spirits described in various faiths’ traditions, such as Satan, fallen angels, demons and jinn, are metaphors for the base character traits a human being may acquire and manifest when he turns away from God and follows his lower nature. Belief in the existence of ghosts and earthbound spirits is rejected and considered to be the product of superstition.

Ceremonial magic

While some people fear demons, or attempt to exorcise them, others willfully attempt to summon them for knowledge, assistance, or power. The ceremonial magician usually consults a grimoire, which gives the names and abilities of demons as well as detailed instructions for conjuring and controlling them. Grimoires are not limited to demons – some give the names of angels or spirits which can be called, a process called theurgy. The use of ceremonial magic to call demons is also known as goetia, the name taken from a section in the famous grimoire known as the Lesser Key of Solomon.

Wicca

According to Rosemary Ellen Guiley, “Demons are not courted or worshipped in contemporary Wicca and Paganism. The existence of negative energies is acknowledged.”

Modern interpretations

Psychologist Wilhelm Wundt remarked that “among the activities attributed by myths all over the world to demons, the harmful predominate, so that in popular belief bad demons are clearly older than good ones.” Sigmund Freud developed this idea and claimed that the concept of demons was derived from the important relation of the living to the dead: “The fact that demons are always regarded as the spirits of those who have died recently shows better than anything the influence of mourning on the origin of the belief in demons.”

M. Scott Peck, an American psychiatrist, wrote two books on the subject, People of the Lie: The Hope For Healing Human Evil and Glimpses of the Devil: A Psychiatrist’s Personal Accounts of Possession, Exorcism, and Redemption. Peck describes in some detail several cases involving his patients. In People of the Lie he provides identifying characteristics of an evil person, whom he classified as having a character disorder. In Glimpses of the Devil Peck goes into significant detail describing how he became interested in exorcism in order to debunk the myth of possession by evil spirits – only to be convinced otherwise after encountering two cases which did not fit into any category known to psychology or psychiatry. Peck came to the conclusion that possession was a rare phenomenon related to evil and that possessed people are not actually evil; rather, they are doing battle with the forces of evil.

Although Peck’s earlier work was met with widespread popular acceptance, his work on the topics of evil and possession has generated significant debate and derision. Much was made of his association with (and admiration for) the controversial Malachi Martin, a Roman Catholic priest and a former Jesuit, despite the fact that Peck consistently called Martin a liar and a manipulator. Richard Woods, a Roman Catholic priest and theologian, has claimed that Dr. Peck misdiagnosed patients based upon a lack of knowledge regarding dissociative identity disorder (formerly known as multiple personality disorder) and had apparently transgressed the boundaries of professional ethics by attempting to persuade his patients into accepting Christianity. Father Woods admitted that he has never witnessed a genuine case of demonic possession in all his years.

According to S. N. Chiu, God is shown sending a demon against Saul in 1 Samuel 16 and 18 in order to punish him for the failure to follow God’s instructions, showing God as having the power to use demons for his own purposes, putting the demon under his divine authority. According to the Britannica Concise Encyclopedia, demons, despite being typically associated with evil, are often shown to be under divine control, and not acting of their own devices.